Note from Riad — Re: Rare Opportunity

❡I like minimalistic designs :)

— Riad

The above is a note added to an earlier post…

The Local Yarn

The Local Yarn

I like minimalistic designs :)

— Riad

The above is a note added to an earlier post…

Good work on the site, Joel. Keep it up.

— Josh

The above is a note added to an earlier post…

Your site’s too good to have comments enabled. Be gone with them!

— walter

The above is a note added to an earlier post…

Greetings from germany and congratulations to this very nice site.

— Dominik

The above is a note added to an earlier post…

I think this is the first time I’ve ever enabled the comment system.

— Joel

The above is a note added to an earlier post…

The continued circumstances of the Regular Vein

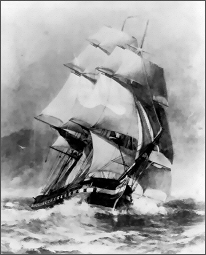

It was Foget’s watch again, the night watch. It was very dark and the wind had died down only a little. He crouched in the crow’s nest, fixated on the pages of a small book, in an island of lantern light barely big enough for a grown man to crawl into.

It was Foget’s watch again, the night watch. It was very dark and the wind had died down only a little. He crouched in the crow’s nest, fixated on the pages of a small book, in an island of lantern light barely big enough for a grown man to crawl into.

Outside and all around, dark and black darkness. There were no stars or moon tonight. There was not a sound below, nor would he much have heard it up there, forty-two feet in the air, if there had been one. It was unusually warm.

The last sand dropped into the bottom of the hourglass, and, as if on its own, Foget’s hand whipped out and flipped it over, smack, on the other end. The hourglass may not flow evenly, but to keep the sands moving is an imperative. No one ever thought about what would happen if someone forgot to flip the glass. No one ever forgot. And you always gave it a good smack to send the first few sands on their way down a little faster, to make up for even the most fractional delay in flipping it over. It was, you can imagine, a very durable timepiece.

Foget sighed and closed his book, but kept his thumb inside to mark his spot. He supposed it was time to give some attention to duty. Looking out, he saw nothing; he even held the lantern up as though the light would in aid in the looking. We now know that light is composed of particles called photons. Well, a swarm of photons bounded out of that lantern, and each one, as soon as it had gone, was seperated from the others and got lost. Some of the photons eventually stumbled up above the clouds, and from there went shooting off clear into space; and some were drowned in the heart of the ocean; and some churned about in ever-widening circles until morning came. But none ever came back to give a report to wide-eyed Foget, to say whether there was an end to this flood of darkness.

He stood there and stared for awhile, then turned about to look in the opposite direction, and what he saw froze him. Something as long and thick as his arm was undulating in the warm breeze, hovering a few feet outside the crow’s nest. He saw only its small eyes at first; they reflected only the faintest hue of dark, dark green. The rest was hardly more than a shadow against shadows. There was something about the way it moved… Of course, he thought, It’s a fish. It was a large northern pike, floating in the air, its body swaying as though it were swimming. Its head was tilted downwards as though it had descended from somewhere higher up.

As he watched, he held the lantern up a little more, and felt a whisper of air in his ear. Another fish had swam quite close to his head; his hand moved up to brush it away, and then his eye caught sight of it moving above him. He tried to keep it in view, the way you look for an insect that has just tried to land on you — “If it comes close again I’ll give it a good brush-off,” he thought — but he could hardly make it out. A couple of times he thought he had lost it, then saw it again in quite a different place. It wasn’t until he gave up looking that he noticed more movement in the darkness close by, and then he realized: there were more than just two fish. There were a lot more. As he looked down to the lanterns on the ship’s deck, far below, he could see their shapes crossing the dim lights.

They were attracted to the light. They were circling him, they were circling the ship.

The lantern — switch it off, switch it off, you fool! But he did something different instead. He dropped it and left. When he looked down, there was the ship beneath him, and his eyes adjusted. He was now himself floating near the topmast. He had gone to scramble onto the rigging and had ended up swimming up into the air. He could see a tight knot of huge fish circling in around the lantern he had dropped — which filled him with relief and dread. Slowly they drew off back into the darkness. Instinctively, he drew back himself.

Foget wondered whether to swim below and get a gun or warn the crew or something. “No no; they’d see me by the lights, or surely bump into me in the dark; I’m as good as invisible here. Maybe they’ll go away soon.” He stayed watching for awhile. “I hope no one on ship will come outsside, or they’re done for.” All the while, he heard, or felt, a very low vibration growing louder. “What is—”; suddenly he was pushed aside by a thick, turbulent current of air.

One wave whirled him aside, then another much more powerful, and the third was a cold shock. He spun in circles, and kicked furiously, trying to get control and get away. Away beneath, all the lights on the ship went out. Something very large had moved very close by.

The clouds parted, and the moon’s rays dappled and pushed around him. He was much farther above the ship now.

A couple hundred feet away, stood a thing whose sheer size transfixed him with awe. It was an eye, a very great eye. But the eye was itself set in the head of a blue whale that would not have fit, it seemed, in a normal ocean of water. Foget, if he could have moved, would have had to turn his head from side to side to view its whole length. It stood, a colossal azure wall, in front of him, blocking out a great part of the stars. Where shafts of moonlight illuminated its skin, it was shown absolutely clean, without a barnacle or a scar.

He took a sudden deep breath like one awaked from sleep. All the fish stirred too, thousands of them, and looked up in his direction. They glared at him. They bristled. Then they shot upwards. Almost before he had time to feel terror, they were nearly upon him. The clouds had descended too, and thickened around him just before the fish reached him. Then his terror increased nine times, for he realized the clouds were made of mosquitos, and they were going to devour him. With frustration and despair, he tried to slap them, to brush them off, then to swim away. But three thousand tiny wings whined in his ears, six thousand tiny feet landed on his skin and a thousand needles began probing for veins. Foget gnashed his teeth and was about to scream: but in an instant the air was as thick with fish as it had been with mosquitos. Foget was enmeshed in a cloud of writhing, snapping pike, who consumed the mosquitos furiously. The mosquitos likewise warred against the fish, even skeletonizing many; others they reduced to horrifying scraps of flesh, barely alive, before being in turn repulsed by other fish. Some of the fish were confused and attacked each other. It was all a blur.

Foget was helpless; of course he would have taken the fish’s side, but he was a clumsy swimmer and the most he could do was try to slap a portion of the mosquitos that landed on him. He kept seeing that gigantic eye looking at him through the hordes of insects - the whale. No expression, no motion, the operation of his huge lungs barely audible.

Far, far down below them, the Regular Vein was on fire. Distant, muffled explosions from the ship’s hold caught his ear. He looked down, and his eyes focused on the hourglass, whose white sands were nearly gone.

Then whatever had suspended this theatre of fish and sailors in the air suddenly gave way, and Foget was falling. Down he went and ever faster, and the fish were all around him falling too. Foget couldn’t decide whether he hoped he would miss the ship or whether he would hit it. Then he saw that the whale was falling too, and realized it didn’t matter, for when the whale hit the water it would be the end of the world.

The whale, the sailor, and thousands of dead and living fish, all hit the water at exactly the same moment. The sound was sickening.

The last sand dropped into the bottom of the hourglass. Smack, Foget’s hand whipped out and flipped it over. He sat up, rubbed his eyes, and it was morning. It was colder, and raining. His book showed signs of having been set on fire by the lantern - and so did his hair, although he didn’t know it yet.

Bill Norr, who had just come up to the crow’s nest for the next watch, observed the burnt book and hair, the knocked-over lantern, the bloodshot eyes of the bedraggled, wet sailor.

“Oh sticks. Not again.”

Foget looked at him with wide eyes, and was about to speak, but he stopped, leaving his mouth hanging open. Bill motioned him to climb down. As Foget got up and looked out over the ship, he saw it was covered in fish bones.

— JD

“The whale fell directly over him, and probably killed him in a moment.”

—Rev. Henry T Cheever, The Whale and his Captors

Roger stood on the deck, undoing his necktie and looking for the cat. Too late, he spotted it — nonchalantly trailing a young woman down the sidewalk! Call out, give chase? How awkward, he thought. Frozen in indecision, he watched them walk away together.

Back aboard the Regular Vein

It was Friday morning, and the seas were choppy and breezy, and the blue sky was field to a huge rank and file of puffy clouds. All creation, from top to bottom, was marching west by northwest, and not a speck of land in sight. The hands on duty were doing just that - their duty - and precious little more; not much special attention being required in these regular seas, on this regular ship.

All of a sudden, the Port-Sands Mariner came busting out of the forecastle, rolling up his sleeves and whistling, and looking around for someone with some spare time and a fresh ear. Everyone was instantly busy as soon as they saw him. Foget, scrubbing the deck, fell to it with renewed focus. The others were calling to each other and swinging about on the rigging with their long lemur-like arms. One fellow was repairing some tackle, and instantly remembered that he needed a small kind of a hack-saw that he had left down below. None of this was lost on Port-sands.

“Why all the fuss all of a sudden, hey? It an’t so blowy out here as to ratterfy all this fuss! Stand down, there! Don’t you know what is good for you? Come here and learn from one of your betters! Y’hear!”

“Bark harder, wharf-hound! We’re not home!” shouted Bill Norr, heartily amused by his own pun. “Wharf! Wharf!”

“You heathen disgrace!” A pause and a furious search for a repartee. “There’s not a regular vein in your body!” Loud guffaws from the opposition. “Heave to, lads, in-deed,” muttered Port-Sands. “You’d think there was a squall on. I’ll be blowed if it’s so blowy as all that.”

Standing away up on the quarterdeck, the silhouette of the captain and first mate could be seen against the bright eastern sky of the morning, looking for all the nation like wooden fixtures of the ship, as it heaved up and down with the waves. “It’s no good, Mr. Port-sands,” called out the first mate. “It’s nice out. No one wants to listen to your yarns today. It’s not human nature. It would be a waste of the outdoors. And besides, it’s creditable in you that you inspire them to such diligence.”

“‘Diligence!’ It’s only their slothful indolent natures setting them on to working so! ‘Diligence’ my eye…” Port-sands strode over into the forecastle and his bunk.

After a short while, he reappeared on deck, carrying some pants and a sewing kit. He sat down next to where Foget was scrubbing. He tightened his lips and started away with thread and needle. Foget was smiling to himself; Port-sands just kept his eye on his work. “You know what’s wrong on this ship?” he began. “Consideration. There’s nobody up there has the smallest, most metric pint of consideration. I’m not just talking about affable helpful considerate; I mean the genuine general article of thoughtfulness.

“Take this ship, for instance. Where are we headed? West-northwest. Why? Nobody knows. Does anyone care? If they did, they’d ask questions about it; they’d be curious. They’d have a appetite for hearing about what we may run into. They’d want to hear from someone who’d been there before. They’d pay attention. They’d mark a fellow’s words and not mind whether it was nice outside. They’d master their passions. But see, they don’t consider it. Consideration. And there’s only two ways to see that clear, if they really have none of it.

“One, simpleness. It isn’t in their capacity, maybe? But they can play checkers, and almost every one of em could read and write the log on this mouldy boat! So much to say for number one. Two, they choose not to think on it. It’s the only alternative. So there you are. They choose to stop their ears, which is a inexcusary point of willful sinful indolence in them, and so I affirm it when I say they redouble their work out of sheer slothfulness.

“But why won’t they think on it? Well only consider. Where are we headed? West-northwest. Are we pushing ourselves that way or are we being a-pushed? Why, being pushed, of course. All creation is going thataway. The wind is going west-northwest, the waves are going west-northwest, and the clouds are going - west-northwest also. What can we do about it? Not much. We can swing a few points either way, but there’s no way of going back, not unless all creation goes back too. If you thought on it long, you’d realize we can’t very well go anywhere of our own accord; we’re only tagging along. A frightening thought for a green mind, and that’s to say nothing of exactly what port we’ll land at and what the accounts will look like when we get there.”

Nobody never did anything by halves on that ship, not even morning conversation. And Port-sands was their figurehead, and he did put life into them, with his every noise and gesture. He was a motion picture, a living portrait. You could take a photograph of him at any instant, and any museum would pay a thousand dollars for it - but only because they wouldn’t have been able to hear him speaking.

“Look at the white teeth of the captain, away up on deck there! Why doesn’t he ever stop grinning!”

—JD

“There’s nothing so contagious in a boat as rivets going.”

— Rudyard Kipling (1865–1936)

The female voice on the radio is describing a personal friend of hers, a composer. He is said to be a big, tall fellow, with a huge beard. He has an intimidating presence, but is soft at heart. He can debate philosophy, and yet knows all about what’s new at Disney World. And, as I said, he’s a composer. The woman concludes by saying he is “easily one of the most brilliant men” she knows.

From the way she described him, ticking off a list of his personality quirks meant to illustrate his profundity, I instantly knew we (the woman and I) were two of a kind. I’ve made the same mistake — almost everyone has. We mistake charisma for brilliance.

The people who hold some sway of loyalty over you, you naturally regard as being geniuses. A car salesman isn’t thought any better for going to Disney World all the time; but when our friend the bearded composer does it, it is counted as another facet on his wonderfully complex personality. I have nothing against the bearded composer (never heard of him before); he might really be brilliant for all I know. But, then again, he might be no more intelligent than your average car salesman. The difference is that he has charisma. People with charisma are “brilliant.” People without it are just possessors of cold “intelligence.”

—JD

“I would much rather have men ask why I have no statue, than why I have one.”

—Cato the Elder (234-149 BC)