December 15, 2005

If abnormal means “not normal,” then…

(I think, anyway)

…aboriginal should mean, “not original.”

The Local Yarn

The Local Yarn

If abnormal means “not normal,” then…

(I think, anyway)

…aboriginal should mean, “not original.”

A couple of weeks ago, I drove up north to the cabin to get some pre-winter chores done. The sun sets a lot quicker, now, and it was dark by the time I got past Garrison.

I fiddled with the radio knob, trying to find a voice or a discussion to pass the time. There is that well-meaning guy in his fifties who fills the night hours with sound advice for callers. There is the tail end of the highschool football game. And then, as my fingers turned the knob, I heard a voice I hadn’t heard in a long time. I didn’t know there had been a recording.

***

It was a long time ago, one of those evenings where, at least in the softened hues of our faulty memories, everything went off to good effect, and the whole picture of it seems like a preface for whatever happened later on.

There was this potluck dinner at the Chapel of St. Polycarp the Martyr, over in Pequod Lake. All the Fellows were there (as it later turned out), along with the wives of those who had them. Al Gravesend had brought along a visitor, a man a middle-aged man from out of town. He had curly hair (it was still brown, back then) and huge sideburns — and, what always fixed in everyone’s minds that met him, those heavy-rimmed glasses with lenses as thick as glaciers. If you have read some of my other little pieces, you may recognize that I speak of Mr. Wasserman. Later on we always called him Our Mutual Friend Mr. Wasserman as a joke, because when we first saw him nobody knew him except Al Gravesend.

At some point, while our conversations were rising & ebbing at various ends of the table, this man stood up and began a speech, which none of us were expecting. I think none of us ever could remember how he began it, although we tried to; for we kept on speaking in our own little scattered conversations for a few seconds before we realized that a speech was in progress.

…before I do, I am afraid I must give a line that I think inexcusable in any speech, and that is, ‘When I was asked to speak tonight, I began thinking about what I should say to all of you…’ – well, that is a silly thing to say in any speech. But I say it because I must disclose that I was informed only five minutes ago that I should be speaking here, now, and I mention it to forewarn you. You can expect me to flounder a bit.

I think, the, the general consensus is that things in general are in a very bad state. I know you were hoping to forget about it when you came here. The national leadership is floundering, or nonexistent, or a mythical concept, depending on who you ask. Natural disasters are everywhere. The nihilists are all afoot again, in all the news headlines and (seemingly) at every bus stop.

Worse than this, I think, is this, this atmosphere of…righteous indignation. There is a lot of it. I see some of you are cringing for fear that I should bring up some controversial subject and spoil the evening. Of course, most of the contentious issues seem to divide us so that we are either on the right or the left side of the pie, but then these other issues come along that separate us along other lines. Such as, this issue of public funding for the Vikings’ stadium is a good example; your own position on it, anecdotally, is not likely to come down to conservative “principles” or progressive “principles,” but simply how much you care about football. Ah, I see some of you nodding your heads – only some, of course. I personally think the deepest real divide today is not between progressives and conservatives, but it is the complete disconnect between the city and the rural. Unfortunately issues like these do not, at the end of the day, help people on opposite sides of the, the “canonical” left/right divide to find common ground. Rather, in today’s atmosphere, they only serve to sever us into more and smaller pieces.

So there are not only problems, but there is this atmosphere of division, such that even natural disasters, which cause death and destruction on incredible scales, in the end become simply a new axis along which to draw a line and choose sides.

Now. There is unity in one area, but it is just the unity which we might avoid if we can help it. It might better be called homogeneity: this homogenizing of our art and culture. It is the unity of the lowest common denominator. All of our music, all of our literature, is blending into an undistinguished puddle. The Internet ought to have liberated us from the stifling power structures of the publishers and recording labels. Instead, the rise in the use of the Internet by promising minds means that everyone compares himself to everyone else and adjusts his style accordingly. I dare to say that if the world is ever again to see somone on the scale of a Beethoven or a Yeats, that person will almost have to have been raised in total ignorance of the Internet.

The world is pretty bad, just now, and you will see it that way in the papers every day for quite some time yet.

This can all be seen from another side, however: our own experience. My family went through some difficult times as well, you know. In our finances, in mistrust and bitterness. Some of the worst problems were like a “death by a thousand papercuts”: petty, painful, frustrating, continuous, senseless, and totally preventable. But a funny thing has happened as time has passed. When we dig out one of our photo albums, what do we most easily recall about those years? Or when we get to talking about those years, do we we vividly recall the anger, frustration and anxiety? Amazingly enough, we do not. We actually see them in a warm light. We remember our brother’s amusing mannerisms now outgrown, our dad’s bushy red beard that he only had for a year (why was that?), the enjoyment of our regular rigmarole. Even things that seemed and felt disastrous at the time are now laughed about, as though we had always realized how funny it was and as if we had always known it would turn out fine in the end.

In fact, we now fall to reflecting on these years past as a means (sometimes) of escaping thoughts of our current problems. Some consolation, eh? But this is not to say that however bad things are now they will only get worse. The lesson is that there is much good going right now that you will likely miss until later. They may seem to get worse – but only because (as a whole) they never get any better.

Mr Kirk once said, there is no such thing as a lost cause, because there is no such thing as a won cause. That is a healthy line to chew on, but it is also helpful, at times, to stop thinking about life in terms of causes.

I don’t know what else to say, and I guess I’m proud to have gotten this far on only five minutes’ notice. Thank you.

***

It was an impromptu speech, and it was the first speech I ever heard him give, and it was of course well-remembered. Maybe you had to be there, but it struck all the right chords with us at the time. Oh Mr. Wasserman, we did remember, even when you didn’t. But you could never have known across how wide and deep a river we would one day look to the memory of those years, and of that evening.

—JD

“The only winner in the War of 1812 was Tchaikovsky.”

— Solomon Short

“Howdy, I am a former Brimson resident, born and raised. What is this all about ? Are you broadcasting from Howell’s corner or in the vicinity ? I lived in the big white house adjacent to George Lake near the boy and girls camp formerly known as Camp House.

“Later, Chuck Juntunen”

I hope you don’t mind if I publish this email. For two Brimson natives to make contact online is astounding. In the early eighties, my father built a house just down the road, right across from the Camp House entrance.

From what I can gather from speaking to Opa and Oma (Abe & Agatha Dueck) your family must have been the ones that lived in that big white house before they did. Since I lived next door, I spent many days in that house, and in the big fields and pine forests around it. Opa pastored a small church that met there, and ran a campground — I don’t recall whether those cottages might have been there in your day.

Howell Creek Radio, unfortunately, is no longer operating, since they sold the equipment to Carl Snellman, who is trying (unsuccessfully so far) to become an affilliate of WELY in (you guessed it) Ely.

Leaving for up north today, spending the week at Lake Inguadona. No headphones, no cell phones, no laptop. Lots of fishing. Tactical wargames in the woods. Frosty’s.

Reader’s Digest is a cheap publication that is not worthy of your attention.

It has degenerated into a cycle of the same four topics: dieting, mortgages, celebrities, and medication.

A magazine with a title like Reader’s Digest ought to have some kind of literary interest. It ought to introduce new ideas. It ought to improve your command of the language, and to inspire by some amount of genius, however small.

I wouldn’t be so bitter about it if the magazine didn’t pretend to be something it isn’t. You don’t ordinarily get annoyed with a saltine cracker, but you do if it sells itself as a goblet of grape juice.

(Trying to make the 68% vitriol quota for the year)

I love Minnesota. I hate the cities, thoroughly, with both sides of my brain.

I live and have lived, for many years, near the Twin Cities, Minneapolis and St. Paul. The Twin Cities do not represent anything uniquely Minnesotan, only another iteration of the homogenized American strip-mall culture.

The real joke with these two particular cities is the big pretend that they are vastly different from each other. Yes, Minneapols has “night life,” which I’m told St. Paul doesn’t, and it has this old brewery-turned-office-space where I used to work (pictured above), and it has the cherry and the spoon. And then St. Paul has more trees and trails and almost no tall buildings, and it’s on the other side of the big line-in-the-sand we call the Mississippi River, so it must be really different from Minneapolis, right?

But both cities are the same as each other, and as every other city, from Boston to Dallas to Portland. The scenery is the same. They are an arm of the national franchises and a forum for the same national talking points.

But Minnesota does have some nice areas. They are wide and beautiful. They thaw and make music in summer; and in the winter, when there is no wind and the snow is falling hard, there is total and absolute silence.

“Many a man has fallen in love with a girl in a light

so dim he would not have chosen a suit by it.”

— Maurice Chevalier (1888-1972)

The door opened and the unavoidable fellow walked into the office. Not that I hadn’t heard him coming long before he reached the door. In his youth his ankle-joints had cracked and now his knees and hip sockets did too, while he walked.

I offered him a seat and he took it, though not where I expected. He perched on the big conference table, resting his back against the bare brick walls of the office space. This was his first visit to me at my new job, a new office. He seemed quite curious about it as he was looking all around, noting the furniture and files, but he asked no questions. Only nodded to himself; everything, unfortunately, was as he expected it to be.

“Very nice situation,” said Mr. Edwin Nathanael Dowdley, leading us off at last. “Very nice place. Very nice painting.” A painting of a large ship, with a wide-eyed sailor at the helm, hung on the wall just above his head.

“Thank you. Brought it out of storage to break up the monotony of the fortress walls, as it were.”

His starched collar crinkled as he turned up his head to look at it, his shoulders still resting on the brick. “You don’t mind that fellow’s rather probing gaze?” he asked, referring to the aforementioned sailor, who might have been straining to see rocks through the storm. It was as though he was looking right at you but couldn’t yet see you. “I find it reminds me to stay focused on my work.”

“Ah. Very nice.” Repeating himself.

He spoke up again; “I suppose you enjoy it in here.”

“Well. It’s funny, I tell everyone I don’t, but actually I do. I really did like working outside, but to myself I must admit I like this better.”

“Pish, I can do better than that. You may have appreciated construction in a moral sense. People you admired preferred it. You knew you had it coming so you ate your potatoes and told yourself it was good for you. But you never enjoyed it.”

“I don’t know, you may be right, only partly though. There were points about it that I really did enjoy.”

“Well, don’t you enjoy this as well?”

“That’s just it. It certainly is more convenient. It pays better than anything I’ve done. The environment is clean and orderly, the industry on the rise, the people professional. And it seems more in line with my gifts to be working with my head instead of my back.”

“Sounds too easy, then, is that it?”

Here there was silence, as I continued to stare at the floor, raise my eyebrows, and think.

“You’re just never happy, are you. If something is hard, you complain that it’s hard. If it’s good and satisfying you worry that it’s too easy.” He swung his lower legs as they dangled off the conference table, and from inside his two trouser-legs came the unmuffled one-two popping of his knees, crick-crack.

“I don’t know. The problem is ideological. I see the country dying of complacency, mediocrity and materialism. Instead of a few thousand pioneers we have three hundred million people who always take the path of least resistance. And here I kind of feel as though I’ve gone and exemplified the problem. In construction I was forced to confront my weaknesses. It added weight to my character. This new situation, I feel, plays more to my weaknesses of preference than to my strengths of proficiency.”

“You say it added weight to your character, but it only made you different from everyone else.”

“But that ought to count for something. Everyone has an office job.”

“No, they don’t.”

“Well in any case, what the country needs is, someway-somehow, we have got to get back that pioneer ethic. People need to attempt something big, you know; trans-generational. People have to get back to that sense of starting over from scratch, where the odds are long and the work hard, but the opportunity limitless for those who come after. Those who come after – we have to remember that we are not in this for ourselves, Mr. Dowdley.”

“If you think taking this job was a betrayal of all that, and I’m not sure I see how it was, then why did you take it?”

“It’s complicated, but only because I try and justify it to myself. But I can say this: these people do seem to genuinely need my help. And if I left I don’t know how they could fill the gap without a lot of extra trouble.”

“That ought to be enough right there – why think about it any further!”

“Because if you turn your back on your ideals you run the risk of becoming a moral vegetable.”

“You want to know what I think?”

“I know what you think.”

“Well then?”

“I know I want to believe you, therefore I refuse to believe you, so you can talk all you want, but I’m not listening.”

“Your problem is that you think too highly of yourself.”

“Yes, it would make everything much easier if I told myself nothing I did really mattered in the long run.”

“Ah now, wait—” holding up one finger: “It’s all well and good to think of the example you set for those-who-come-after, but you’ve gone further than this. You’ve created a guiding principle based, on well, nothing really, and you imagine it’s up to you to lead the way for everyone else. And this you would not have done if you had a sensible perspective on yourself.”

“If the principle is correct than all of this is irrelevant.”

“If the principle keeps smacking your face into a wall then shouldn’t that signify a problem with the principle? If a map takes you down a dead end, is it a good map?”

I had to admit he had a point there. This particular rule of thumb was even nearer to my heart than the pioneer thing. Hadn’t I been smacking my face into the wall, so to speak, for two years? I was at a crucial season of life; I didn’t think I could spare the time for more dead-ends.

“Well, you may have something there, but you know, part of the difficulty in proving the principle is that it calls for the sacrifice of short-term gain and does not even promise success within one’s lifetime.”

“You want your life to count for something after you are gone. I can understand that. Why you think you must hand-hew your own set of ideals for doing so is beyond me. The pioneer ‘age’ is gone and there is no use trying to bring it back. It would be out of place. The pioneeers worked not for their own happiness but for their posterity. And you, the posterity, have turned them down on it.”

“But this is all very grandiose,” he continued. “I repeat what I said earlier, that you think too highly of yourself. You are really not concerned about sticking to your philisophical guns. You’re just worried that you’ll miss your greatest potential. Only give some thought to helping others hit theirs, and stop this navel-gazing.”

“Actually, I’d be happy if I could just avoid ending up—” …but my eyes met his, and his sparked of thin mischief.

“How close can you steer toward the rocks and still miss them, eh? Ha ha ha!” Cracking of knuckles. “Not knowing – that’s half the excitement.”

He was getting up off the table now. “You know, your life is extremely exciting. You watch all these elephants fighting in the sky, worrying what will happen when one or the other of them falls on you; and when they do, so far from crushing you, they hardly even make a mark in the grass. You ought to be grateful.”

Well, I am; very grateful. But not about that so much.

—JD

“Preserving health by too severe a rule is a worrisome malady.”

—Francois de La Rochefoucauld (1613-1680)

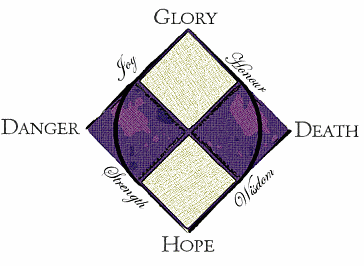

Here is something I have had in my pocket for a couple of years.

Why do Hope and Glory lie on the vertical axis?

Because the movement from Hope to Glory is a process of struggle.

Why do Danger and Death lie on the horizontal axis?

Because the presence of each is a constant.

Why are the optimists right about Hope?

Because without faith there is no achievement.

Why are the optimists wrong?

Because no goal of man is certain until it is actually achieved.

What is the greatest hope?

The greatest hope is that which induces the most action, against the greatest danger.

What if there is no hope?

If there is no hope then there is no danger, no death, and no glory. The scenario is forfeit.

How can you know whether there is hope?

If there is no change and no action then there is no hope.

Why are the pessimists right about Death and Danger?

Because to ignore or make light of them is foolish.

Why are the pessimists wrong?

Because without faith there is no achievement.

Why is danger continually present?

Danger must always be present because your time is limited. Danger is inversely proportional to time remaining. If

you had an unending supply of time, the degree of danger would be zero.

What is the greatest danger to a man or woman?

The greatest danger to a man or woman is their own tendency toward mediocrity and selfishness.

What is the fundamental danger?

Lack of time. If time is in infinite supply, any danger can be certainly overcome. But time is always limited.

Where is the danger when death occurs?

Death eliminates danger because the struggle is ended.

Why is death desireable?

Because death is the shortcut through struggle.

Why must death be avoided at all costs?

Because without struggle there is no glory, and forfeiture brings shame.

Why do many of us foolishly desire death?

Because of our tendency towards mediocrity and selfishness.

Why do many of us fear death?

Because of our tendency towards mediocrity and selfishness.

Is glory an inevitability?

If there is an unending supply of time then glory is certain. Where time is limited, glory is uncertain, and there is danger of failure.

So, can I ever be certain of glory?

Again, while glory is temporally uncertain, it is ultimately certain. Therefore you can only be certain of glory if you hope after something of timeless significance.

Why, then, do not all of us hope after something of timeless significance?

Because of our tendency toward mediocrity and selfishness.

What is of timeless significance?

Anything that will outlast your death is of timeless significance.

I tried to maintain parity between questions and answers, but at the end of the piece there are always more of the former and I haven’t been able to get rid of them entirely.

—JD

“Let’s have some new clichès.”

— Samuel Goldwyn (1882-1974)

I just turned twenty-four, which is the number of years after.