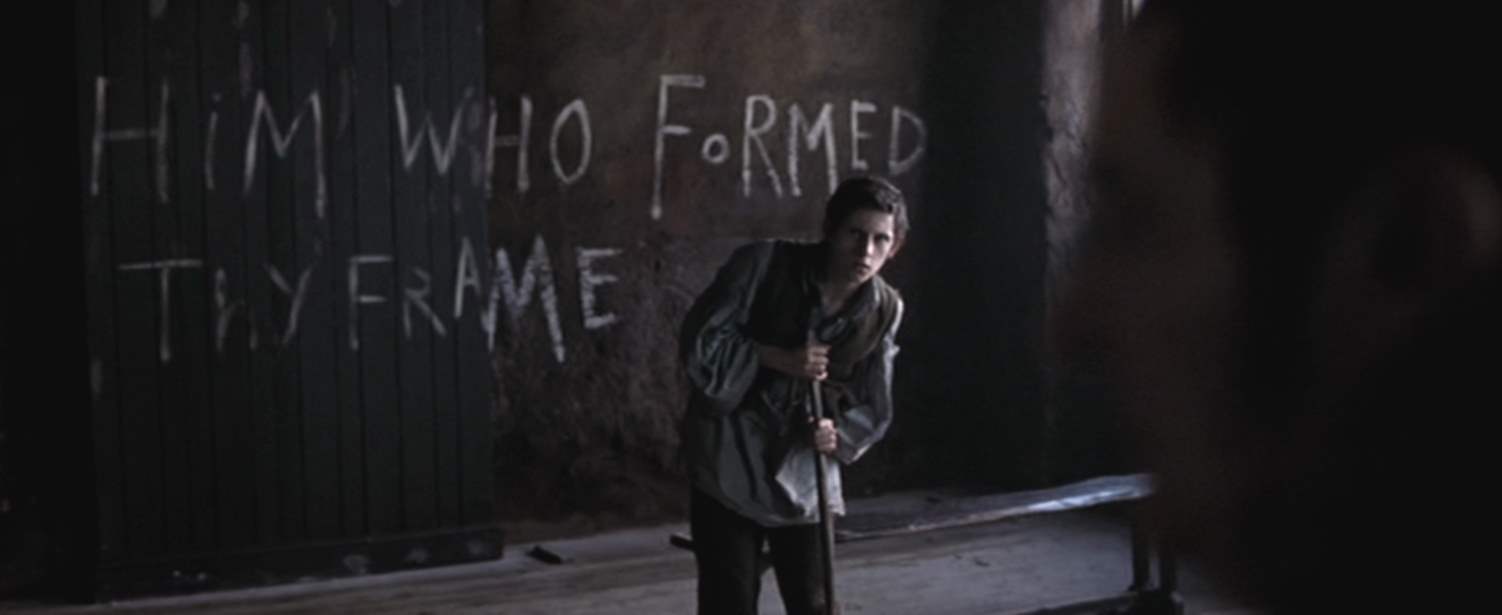

Smike, the worthless delinquent rebel of Dotheboys Hall, whose poor character required constant physical discipline

At the end of Charles Dickens’ Nicholas Nickleby, when the Squeers family’s abusive school for boys is finally broken up, there follows this very sad scene:

For some days afterwards, the neighbouring country was overrun with boys… There were a few timid young children, who, miserable as they had been, and many as were the tears they had shed in the wretched school, still knew no other home, and had formed for it a sort of attachment, which made them weep when the bolder spirits fled, and cling to it as a refuge. Of these, some were found crying under hedges and in such places, frightened at the solitude. One had a dead bird in a little cage; he had wandered nearly twenty miles, and when his poor favourite died, lost courage, and lay down beside him. Another was discovered in a yard hard by the school, sleeping with a dog, who bit at those who came to remove him, and licked the sleeping child’s pale face.

This is a good picture of what happens to those in a cult1 when it comes crashing down around them. I see iterations of these scenes playing out all around me, and to some degree within myself, amid the breaking-up of the particular Christian-flavoured fringe in which my wife and I grew up.

To be clear, there are two senses in which a fringe like IBLP can be said to resemble Dotheboys Hall: the theological/philisophical sense first — how does the cult paint the world to its believers? — and secondly, the personally-abusive sense: the radical and repugnant harms practised upon the weak by authority figures. In many families, such as my own, there was comparatively little to no personal abuse. Other families had it much worse in that regard.

But we all experienced the effects of a false, shallow understanding of God, and of the world; and this is where it gets tough to write or talk productively. Because the whole problem with institutionalized ignorance is that even when you break free of it, you have no sound baseline to return to, or to contrast it with; you simply have nothing.

The Village is another good picture of what I’m talking about (in fact, probably a better one, since most of the parents aren’t depicted as Squeersian caricatures of evil). It may not have been a critical success2, but when we saw it, it felt personal; I still can’t be sure M. Night Shyamalan did not write it specifically for us and about us. Supposing there had been a sequel, Ivy Walker’s an escaped villager’s3 life would in many ways resemble ours. She would now, for example, see the colour red every day — in decorations, in people’s clothing — and in order to function, she would have to overcome a lifetime of being conditioned to think that red itself is sinful and would attract evil. If she kept contact with any of her old set, she would know that they were all going through the same process at wildly different rates. There would be a lot of additional social calculus around their reactions to the colour red, and any possible effects on her relationships with each of them.

Most of the headlines now flying around about our particular situation are about personal abuse of various kinds, and those stories need to be told. But far more horrifying to me — and perhaps just as common, if not more so — is the practice of teaching a child a thing is morally wrong when it isn’t. It may be done out of honorable motives at least as often as out of selfishness, but either way, this is how you mess a person up. This is how you retard their ability to give and receive love, and their capacity to relate to other people, in such a way that, even if they someday realize it has happened, they will spend decades puzzling it out.

Anyhow, when the institution comes crashing down, you see this radical disorientation that manifests any number of ways. If your experience was more painful, you might spend an inordinate amount of time and energy criticizing or mocking the old regime, which is sad in its way, but understandable and even necessary.

I left it behind (in terms of my theology and politics) several years ago, more because I was attracted to reality than because of any loathing for my past. For some time I imagined I was enlightened or intelligent for having left it all behind; but at last, it turns out I’m neither. I’m just an ignorant wanderer. I’m like the boy in the paragraph above, who wandered twenty miles, carrying a cage with the dead bird of my theodicy still flopping about inside. Like any lost child, I have a lot to learn, but the first thing is to overcome my intense cynicism and mistrust of those who might be able to teach me.

They were taken aback, and some other stragglers were recovered, but by degrees they were claimed, or lost again; and in course of time, Dotheboys Hall and its last breaking-up began to be forgotten by the neighbours, or to be only spoken of as amongst the things that had been.

Dotheboys Hall makes an excellent picture of a cult. As headmaster, Squeers sets himself up not as a simple administrator, but as a spiritual authority, propping up his brutality with moral maxims and high-minded principles. He uses this authority to set severe limits on the physical and mental range of his students’ world, and within those limits erects a flimsy ethical structure that just so happens to align very well with his business goals. That is what I believe we mean by the word “cult”, no matter what means are employed or how unevenly their effects are felt.↩

Roger Ebert’s well-known hatred of The Village is multifaceted, but it seems centered around the twist being too mundane, too obvious: “To call it an anticlimax would be an insult not only to climaxes but to prefixes. It’s a crummy secret, about one step up the ladder of narrative originality from It Was All a Dream.” It’s a valid opinion, but what it demonstrates to me is that Ebert, happily, did not grow up in a cult. Of course the premise and the twist are mundane for a normal person. For the ex-cult member, though, they are powerful — not because the ending is a surprise, but because they match our experience so frightfully well.↩

Thanks to Anna for reminding me that Ivy Walker was blind — she wouldn’t be able to notice red or any other colour.↩