The Settler

You can hear an audio production of this poem, which was written for the Howell Creek Radio podcast.

The Local Yarn

The Local Yarn

You can hear an audio production of this poem, which was written for the Howell Creek Radio podcast.

Listening to the audiobook of 1776 by David McCullough lately, I was struck by how many of the common soldiers in the ranks of both the Americans and the British kept journals. Even more interesting was the content of many of the entries. In addition to conventional entries about marches, fights and privations, they often wrote things like “nothing to report,” “cold,” or just “Same as above.” For whatever reason, with no offical order to do so, even those lowest in the ranks felt it was important to document what they saw, no matter how seemingly unimportant or routine, or how unlikely anyone was to take note of it. They made a point of writing something down even when there was nothing to write down. The fact is that now, two hundred and thirty years later, their accounts give us an extremely valuable balance to the officers’ “official” perspective (and the newspapers’ extremely stylized perspective) on the events of their time.

This inspired me to buy a separate journal for use at work. My plan is to simply write down a bare-bones account of what happens every day in the office, or wherever I am working, from now until the end of my career. It occurred to me that I would liked to have started on this five years ago, and have it handy to look back on – a lot of significant things have happened in that time. I also thought of how much I would have liked to be able to read such a journal from my grandparents. This made it all the easier for me to just buy one and get started.

I wanted a fresh book to get started with, and I chose one of the limited-edition Peanuts journals partly because Charles Schultz is from around here and partly because Peanuts seems to fit on many levels. I do already have a book that I have used for work purposes, but it is mostly filled with crossed-out todo items, phone numbers, and sketchily-abbreviated meeting notes.1 I also have a personal journal which this does not replace for obvious reasons.

I wanted a fresh book to get started with, and I chose one of the limited-edition Peanuts journals partly because Charles Schultz is from around here and partly because Peanuts seems to fit on many levels. I do already have a book that I have used for work purposes, but it is mostly filled with crossed-out todo items, phone numbers, and sketchily-abbreviated meeting notes.1 I also have a personal journal which this does not replace for obvious reasons.

The idea is:

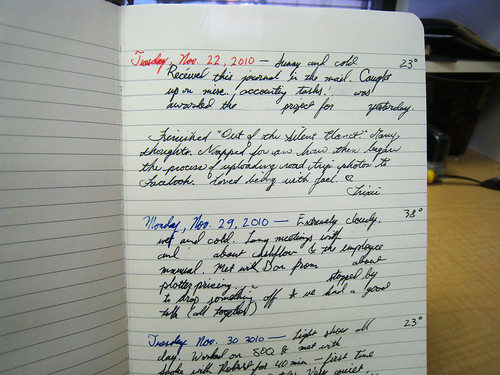

A representative sample from the first few days. “Trixie” and I hang out with each other at our jobs whenever possible since we get so little time to spend together. I also like to note the temperature and the weather.

I don’t know exactly what use this information will be, whether it will ever be deemed important or even what will ultimately be done with it.2 Those are exactly the kinds of questions the rank-and-file journalers didn’t concern themselves with. What they recognized is that simple, regular observations have inherent value, both to us individually and to our collective memory.

In addition to whatever personal value this may provide in the future, I’ve found that writing a work journal in this way has the following effects:

—JD

1 These probably have just as much historical and “rememberance” value as anything else. In my case, I want to provide myself with opportunity for observation and gloss over the details of specific tasks. There is no single correct mix, but this one fits my priorities and more closely matches the practice of the 1700s-era soldiers that inspired me to begin with (I’ve always liked old things).

2 Realistically, I expect that my journals will be of interest to my family for a few months or years after I’m gone, and stored in boxes thereafter. I think ideally there would be a place where families could donate such things to places that could archive them permanently, and make them available for later research.

I don’t have a problem with technology’s place in our lives at all. I have, however, a growing problem with the back-lit screen, and a growing desire to see it, if not abolished, then at least dethroned and humbled.

I don’t have a problem with technology’s place in our lives at all. I have, however, a growing problem with the back-lit screen, and a growing desire to see it, if not abolished, then at least dethroned and humbled.

Back-lit screens are something we’ve grown very used to without realizing what they’ve done to our way of thinking. They are hypnotic, arresting, and distracting. No matter how small a back-lit screen is, it quickly occupies your whole field of vision. It ruins your sense of your surroundings in the same way a flashlight ruins your night-vision. It is, to my mind, the single biggest reason that we find ourselves trying to divide our attentions between a “real-life” world and a “digital” world - a dualistic mindset that causes eventual burnout.

In the beginning, computers featured blinking lights, fans, buttons, switches, paper punch-cards and printouts, all of which we as humans can “read” and connect with just as we would with any other physical object, without having any sense of escaping from reality.1

This video is from a 1969 Disney movie, and I do not mean to use it as an example of the state of serious computer science in the 1960s. [Update: the original video from The Computer Wore Tennis Shoes has been pulled; I’ve replaced it with the Willy Wonka video linked at the end of this paragraph, as it illustrates the same point.] I do mean to use it as a rough example of where computers fit into the popular mindset of our culture at that time. You can see, from listening to Professor Quigley’s line of reasoning and his use cases, that in 1969 the computer was seen primarily as an appliance, like a washing machine. It had brains and memory and could be fed instructions - but the whole point of it all was that it could augment your everyday life and make it more convenient, e.g., open the door to let your cat in while you were away. The highest possible use envisioned for the computer at that time was as an advanced calculator - i.e., still an appliance, just an appliance for NASA engineers this time instead of housewives. You used a computer as you would any other appliance, by flipping switches and pressing buttons, and the results were typically imagined as a printed piece of paper in plain language.

Another movie clip, from the 1980s this time. Look at the change in the popular idea of What Computers Are All About. Now the computer featured a back-lit screen: sort of like television (already a highly-evolved alternate reality in its own right) except you were interacting with it.

When the back-lit screen came on the scene, computers ceased to be appliances and became windows into an alternate universe.

The movies of the 1980s reflected fascination with this idea, and, twenty years later, the movies of our decade still reflect this fascination. The backlit screen was the feature that changed popular conception of computing technology, and it created this jarring mental framework that leads us to think of computer-based interaction as involving an “alternate reality”. We have been trying to escape from this idea ever since.

I seem to recall seeing a lot of articles online about “blogging burnouts:” people who started blogs or personal websites back in the day and now never write on them any more, and either feel guilty about it or just consciously decide to move on. Many of the people who used to find their websites and blogs to be great outlets for creative expression no longer seem to have the time for them - no longer seem able to make time for them.

There are still plenty of active bloggers, sure, but there is also a lot of turnover among us. It seems like very few people keep at it for a really long time. This, to me, is another indicator of how wearing-down this alternate-reality thing is. It’s addicting but ultimately unsatisfying. There will always be participants, but eventually you will experience burnout. You can’t make yourself stay in an alternate reality for too long; even many self-described geeks eventually want out.2

At the same time, though, we find it very hard to give up the web, that thing that we can hook up to our brain and instantly know what our friends are up to and what the name of that actor in that movie was. The web works beautifully as an add-on to our normal lives, but suffers in the prison of the back-lit screen. With the back-lit screen, the web is a place you can only see when you stare inside your computer or your cell phone. Your eyes have to focus continually, and your pupils have to adjust to different light levels to see into this web. It is its own dimension, utterly separate from what you see when you look around the room or out the window.

The back-lit screens have splintered and multiplied, and are no longer chained to a desk. Now you can have the web in your pocket, on your phone, on your coffee room table. This goes a long way toward making the web less and less a separate reality than a feature of the normal one. Indeed, our language has already adapted to reflect this - the word ‘cyberspace’ already has the sound of a goofy anachronism, impossible to utter without irony. The original flaw of the back-lit screen, though, remains in effect: it forces you to experience connectedness only by ruining your day-vision. In the end, the iPhone is still just as much a part of the old ‘cyberspace’ paradigm as the green-screen terminal in War Games: a dimension unto its own, an end unto itself, a prison.

Some time ago, I, like many others, grew tired of writing for the back-lit screen. But I tried podcasting and, surprisingly, I kept it up, because I found I could create an experience that didn’t tether people to their computers: something that you could listen to while out for a walk, or while driving to work. This appealed to me a great deal. It’s the same reason why I’m interested in publishing for Kindle: the variety and immediate delivery of the web without the eye strain, without the glowing screen that ruins your day-vision for your immediate surroundings.

My dream is to produce audio experiences without ever once having to sit down in front of a back-lit screen. But an even bigger dream is the idea that one day, you will be able to listen without ever sitting down in front of a back-lit computer screen either. When the back-lit screen has followed the CRT down the path of obsolescence and electronic ink is everywhere, the web will flourish only as a delivery path for things to wind up on your table, in your armchair, your picnic table and your car.

—JD

I hold up the original radio as the most natural interface of any communications technology man has created so far. It has simple controls which map naturally to their functions and are easily understood, and you process its output through your ear, with no special interpretation necessary and with very low cognitive overhead - even compared with, for example, television.↩

There are so many of these kinds of posts being written these days that I can just Google ‘back to pen and paper’ and pick one at random.↩

I taught myself to program computers out of library books in my early teens, and to design websites by age twenty. Yet I decided not to pursue a computer-related career. I still wonder if that was a smart decision. But the main reason was inscrutability. The further I progressed into computer technology, the more I encountered problems I had no possible way of solving. I gradually came to the conclusion that all technology is basically broken at some level, and that technical savvy consists of elaborate workarounds, and a tolerance of shoddy design1 — whether at the user interface level or the IDE level or the memory-management level. Some people are geeks enough to accept or even enjoy working in such a field; the idealist in me at age 20 wasn’t able to stomach twenty years of having creative solutions shot down by unaccountable, unfixable, and inscrutable technical problems.

The hacker in me found this post entertaining and even easy to follow, despite the fact that I have only an intermediate understanding of the technologies involved. The compulsive chronicler in me appreciated the fact that Piotr took the time to document an obscure problem, the troubleshooting process, and the solution, and work in some people lessons while he was at it. No matter how obscure the problem is, someone else will have it again sometime; and now a trip to Google is likely to bring them to Piotr’s explanation and save them a world of trouble. It’s exactly the kind of thing for which I started my Notely blog.

The thing that caught me most however, was the customer-service dimension of the solution. For the customer, the problem must have been annoying — because of the particular performance issue, yes, but also because it seemed totally unaccountable and unsolvable. They bought a box, plugged it into their network, configured it properly, and everything ground to a halt. From their point of view, everything pointed to a defective product — yet when Piotr fixed the problem (without blaming them for their unpatched server, the real problem) they went on to buy several more products from his company. Why was this?

I can tell you for certain that when an IT worker demonstrates an ability to see into and fix random problems that pop up like this, they set themselves far apart from the pack. Most IT workers are just workaround-tolerant hacks in disguise, and this tells in their2 proposed solutions: try swapping this out, try rebooting, try installing updates. Even when these “solutions” work, they lack satisfaction because it’s obvious that no one understands the problem. There is very little to distinguish the troubleshooting from mere voodoo, and I find it regrettable that a profession which purports to deal in logic and technology should depend so much on superstition.

In short, Piotr’s post rekindles in me a hope that the “voodoo veil” in technology can be pierced after all. It somehow reminds me of how getting police diver training taught me that things are not irretrievably “lost” once they fall into a lake: you just need the equipment and the expertise to get all the way to the bottom of the problem space. Perhaps all IT lacks is effective mentoring connections between the experienced and the newcomers. But that is a whole ‘nother issue.

—JD

A lot of this may seem old hat, but please bear with me until the end.

When you first start browsing the World Wide Web, things look kind of like this:

The little squares are websites, out of which new information, ideas and pictures bubble and trickle like water from a spring.

Eventually, the World Wide Web separates itself out into two distinct categories. The first, shown on the far right, is of sites you only occasionally remember or check on, or run into because someone sent you a link - the spare-time blogs, the news sites that only occasionally produce an article that catches your attention, the odd Vimeo channel.

The second, shown in the middle area above, is of sites you visit nearly every time you open your web browser. If your web browser is a palantír then these sites are rather like Barad-dûr, in that once you’ve visited them once or twice, they hold your attention, and you keep coming back to them.1

For people who use the web for reading, for Items of Interest, this middle group includes more than just Facebook or Yahoo Finance or online shopping. It includes sites like kottke and Tumblr and Lifehacker - sites that mainly collect interesting links from other sites, rather than being creative in their own right. They act as a filter. You keep coming back to them because they do all the work of finding the interesting items for you. These “filter sites” are represented by the long thin rectangles. To the reader, they are a mile wide and an inch deep.2

Here you see a different kind of site now in the middle area. It’s in the middle, but it’s not a filter site; it is “interesting” in and of itself. Whoever maintains it is mostly writing his own content, taking his own pictures, and generally fueling the endeavor with his or her own creativity. Of course, there are lots of these kind of sites on the far right, but the difference is that the ones in the middle are both good at creating interesting things, and at doing so regularly.

If you’re still reading by now, you’re probably someone who has an interest in creating a site like that polka-dotted one above, or in moving your site from the right to the middle. You’re actually the ones I’ve been talking to all along in this post. So all of that was to say this:

The people who make the polka-dotted sites are able to do it only because they have time to create, healthy attention spans, and the focus to actually finish what they start. And - here’s the kicker - they have these things because they spend less time reading other websites, particularly the other sites in the middle.

All other things being equal, the more you feed off of others’ creative output, the less of your own there will be.

UPDATE, see also Consumption: How Inspiration Killed, Then Ate, Creativity

It still seems funny to me how, these days, you can draw analogies from Tolkien and a decent majority of people will understand them. ↩

I don’t mean that as an insult (although building a site that way doesn’t appeal to me personally); these sites are their own kind of interesting and have large audiences for a reason. The web as a medium tends to favour this kind of format, actually, since the slices of attention the reader must commit to them are far smaller. Whether or not that is a good thing is beyond the scope of my thought here, but I do believe it is detrimental to personal creative activity. ↩

Within the past week, I created a book-style index of everything I’ve ever written on my website, going back to 1999 (see the errata for implementation details). I’ve been thinking about doing it for so long (years), that when I finally decided to do it it took about an hour.

I like this application of the index format, because it allows you to re-explore things after they drop off the front page. It keeps things from disappearing forever. And I’ve never seen anyone else do something quite like it before. But also, like any keyword index, it acts as a low-focus source of ideas; a way to connect random things and concepts without having a preconceived idea of what you’re connecting with—a little spawning-ground of serendipity.

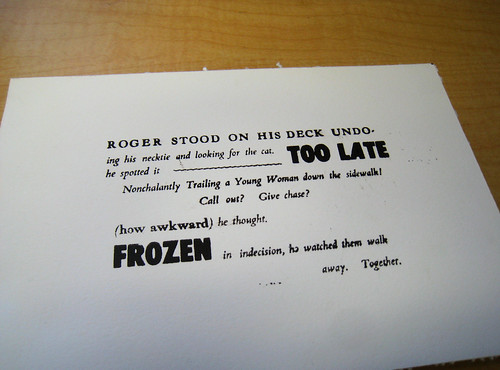

I had an opportunity of doing a letterpress workshop at the Minnesota Center for Book Arts again on Tuesday.

I had only three hours to set the type, buy paper, do my printing and clean up, so I thought I would aim low by setting up one of my marquee fiction pieces, a series of short fictional vignettes each exactly 256 characters long (so they could fit in the Windows “Marquee” screensaver). Next time I am so limited for time, I will just do a business card.

As it was, with a three-hour limit, I was scrambling to get the type set and by the time I was (barely) ready to print, I had only an hour left. I bought and cut my paper, snatched some chocolate brown ink out of the cupboard, locked the chaise into the press, and slapped my paper in without really aligning it except by eye, and started printing. I think the attendant was a little appalled by all the details I seemingly cared little or nothing for, but I was in too much of a hurry to sit down and talk it over with her.

I was especially fortunate that I had no bad letters and no typos. As you can see, it has a kind of hurried, authentic quality to it (putting it charitably). I’m thinking of another run, more carefully prepared, but only if I can sell them, since it would cost me more to rent time on the press. As it is I may end up just putting all the pieces away and make this an extremely limited edition.

Good Night Irene, Scene Four, set in 18pt Goudy Roman, 16/18pt Bembo Italic, and 36pt “Unidentified” type, printed on Crane Lettra 300gsm paper

Someone recently opined that the Postal Service is always having problems. I heartily agree. As long as we’re subsidizing a national postal service, we might as well angle for one that we, as a nation, can be proud of.

Someone recently opined that the Postal Service is always having problems. I heartily agree. As long as we’re subsidizing a national postal service, we might as well angle for one that we, as a nation, can be proud of.

Here are my suggestions to the USPS for how to become relevant again:

(And I told them as much, in response to a four-page survey sent to me by Gallup.)

Yesterday…I went into the room across the hall at eight o’clock in the morning. Dave was already up, huffing around in place and laughing. Peter was still in bed, but his bare arm and open hand snaked out from under the covers, and his plaintive voice: “Would you please hand me a bowl of Special K?”

My goodness, the poem on yesterday’s Writer’s Almanac was morbid, but powerful. When we get to heaven, will we remember pain? Looking back can be helpful – if I was to try and preserve the pain of this life for remembrance in the painless hereafter, I would bring this poem with me to heaven. “__One day, you’ll see. These stings / Are nothing. Nothing at all.__” – in another sense, this is more true than perhaps even the author guessed.

This isn’t about equipment or recording technique, but just the cranky details of publishing a podcast that I have found by trial and error.

If you use nothing else from this article, please: add cover art to your mp3 files. Without it, your episodes show up with blank covers in iPods and most mp3 players! Your podcast will look dorky without it! It’s not enough to add cover art to your itunes feed, you need to embed the cover art in every finished mp3 file. This is easy to do yet everyone forgets to do it.

This approach assumes you have some kind of blog already and allows you to publish your podcast right alongside your other posts, as I do here – in other words, no need to set up a totally separate site for your podcast if you don’t want to. The code examples are specific to Textpattern but can be easily adapted to any other CMS.

http://foopaux.com/atom/?category=podcastery). You can use RSS but Atom is better.Optimize tab, add the SmartCast service to make your feed podcast-friendly. Set the cover art to the URL of your covert art image and add as much description, keywords and categories as you can muster.itpc:// instead of http://. So, for example, you could place this prominently on your website:Subscribe in "iTunes":itpc://feeds.feedburner.com/MyPodcast or "RSS":http://feeds.feedburner.com/MyPodcast<txp:jnm_audio> tag (referred to above) in your post. This is optional.for-syndicate and set it to display: none. Then add a little “helper” boilerplate on the bottom of each post, in a paragraph set to that class:p(for-syndicate). This is a podcast post: "click here":http://site.com/episode.mp3 to download the MP3 audio, or visit "site.com":http://site.com/podcast to listen online and subscribe in iTunes.for-syndicate class will render the paragraph invisible on your website, but it will be visible when imported into Facebook or when the feed is viewed in a newsreader, since these other sites do not import your CSS styles. (If you like, this quasi-hidden paragraph can also serve as the required MP3 link.)