Listening to the audiobook of 1776 by David McCullough lately, I was struck by how many of the common soldiers in the ranks of both the Americans and the British kept journals. Even more interesting was the content of many of the entries. In addition to conventional entries about marches, fights and privations, they often wrote things like “nothing to report,” “cold,” or just “Same as above.” For whatever reason, with no offical order to do so, even those lowest in the ranks felt it was important to document what they saw, no matter how seemingly unimportant or routine, or how unlikely anyone was to take note of it. They made a point of writing something down even when there was nothing to write down. The fact is that now, two hundred and thirty years later, their accounts give us an extremely valuable balance to the officers’ “official” perspective (and the newspapers’ extremely stylized perspective) on the events of their time.

This inspired me to buy a separate journal for use at work. My plan is to simply write down a bare-bones account of what happens every day in the office, or wherever I am working, from now until the end of my career. It occurred to me that I would liked to have started on this five years ago, and have it handy to look back on – a lot of significant things have happened in that time. I also thought of how much I would have liked to be able to read such a journal from my grandparents. This made it all the easier for me to just buy one and get started.

I wanted a fresh book to get started with, and I chose one of the limited-edition Peanuts journals partly because Charles Schultz is from around here and partly because Peanuts seems to fit on many levels. I do already have a book that I have used for work purposes, but it is mostly filled with crossed-out todo items, phone numbers, and sketchily-abbreviated meeting notes.1 I also have a personal journal which this does not replace for obvious reasons.

I wanted a fresh book to get started with, and I chose one of the limited-edition Peanuts journals partly because Charles Schultz is from around here and partly because Peanuts seems to fit on many levels. I do already have a book that I have used for work purposes, but it is mostly filled with crossed-out todo items, phone numbers, and sketchily-abbreviated meeting notes.1 I also have a personal journal which this does not replace for obvious reasons.

The idea is:

- The work journal is strictly “vocation”-related. I just write down what I saw, did, or thought at work.

- I write in it every single weekday.

- Entries can be as short as one word.

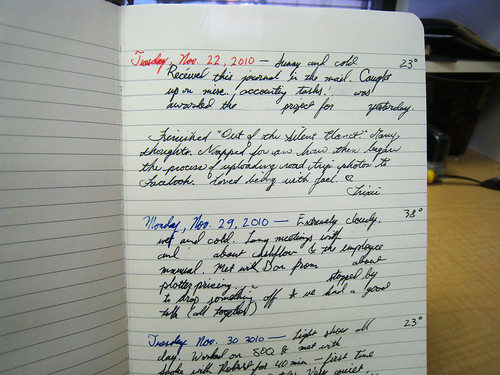

A representative sample from the first few days. “Trixie” and I hang out with each other at our jobs whenever possible since we get so little time to spend together. I also like to note the temperature and the weather.

I don’t know exactly what use this information will be, whether it will ever be deemed important or even what will ultimately be done with it.2 Those are exactly the kinds of questions the rank-and-file journalers didn’t concern themselves with. What they recognized is that simple, regular observations have inherent value, both to us individually and to our collective memory.

In addition to whatever personal value this may provide in the future, I’ve found that writing a work journal in this way has the following effects:

- It helps me to live in awareness of patterns and trends in how I work.

- By condensing the events of the day down from isolated memories into concrete observations, I am better able to mentally “take only what I need” from the day and discard the rest.

—JD

1 These probably have just as much historical and “rememberance” value as anything else. In my case, I want to provide myself with opportunity for observation and gloss over the details of specific tasks. There is no single correct mix, but this one fits my priorities and more closely matches the practice of the 1700s-era soldiers that inspired me to begin with (I’ve always liked old things).

2 Realistically, I expect that my journals will be of interest to my family for a few months or years after I’m gone, and stored in boxes thereafter. I think ideally there would be a place where families could donate such things to places that could archive them permanently, and make them available for later research.