The common Western idea of death is that once you die you are transported immediately to a place of ultimate comfort (or torment), with no intervals. Your consciousness continues seamlessly into the next life, just no longer tied to your physical body.

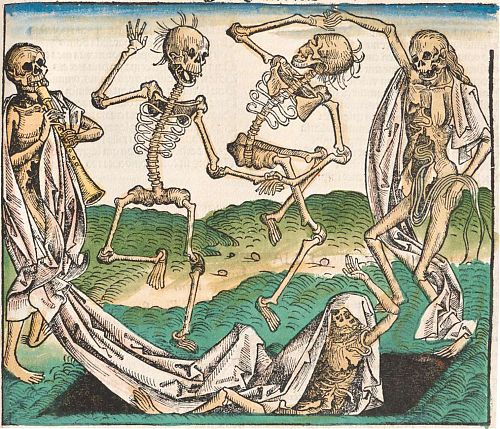

Suppose, though, that while consciousness does continue in some way after death, it remains thoroughly joined to your physical remains. As your body decays, so does your personality, your capacity to reason. Your emotions, having been all along largely the product of your fluids and nerves, transmute ever more into the mute horror which your remains increasingly depict.

This consciousness-in-death was a running theme of Edgar Allen Poe. His genius, in my view, was to paint this horror only at the edges — premature burials, loss of breath, the unwillingness of the “deceased” to actually die — so intimately that we often mistake the edge for the abyss at the center. But in a kind of artistic truth, the madness of Poe’s narrators increases in proportions as that abyss (the experience of actually being dead) is really approached — whenever we see a lady of Usher, for example, or hear the beating of a murdered man’s heart — it is nearly always seen through senses that are themselves being damaged.

C.S. Lewis, on the other hand, gets right inside this idea, describing it in lucid detail in Perelandra, when his villain Weston temporarily recovers his senses and tries to articulate his experience of death:

“…All the good things are now — a thin little rind of what we call life, put on for show, and then — the real universe for ever and ever. To thicken the rind by one centimetre — to live one week, one day, one half hour longer — that’s the only thing that matters. … [Humanity] knows — Homer knew — that all the dead have sunk down into the inner darkness: under the rind. All witless, all twittering, gibbering, decaying… Then there’s Spiritualism…I used to think it all nonsense. But it isn’t. It’s all true. You’ve noticed that all pleasant accounts of the dead are traditional or philosophical? What actual experiment discovers is quite different. Ectoplasm - slimy films coming out of a medium’s belly and making great, chaotic, tumbledown faces. Automatic writing producing reams of rubbish.”

I wonder whether this idea of death is common in other cultures, or times of history. It seems to me something very Other — definitely not Christian, but not exactly Pagan either.

The song ‘Bottom of the River’ by Tom Fun Orchestra seems an appropriate example as well. Interpreted by some as concerned mainly with environmental vandalism, it seems to me more straightforward to read it as the experience of those “beneath the rind”: dead yet conscious, still chained to their remains, enduring a never-ending passage of time where light is distant and the idle time-marking movements of the living all too close.