The Unbearable Lightness of Web Pages

Joel Dueck

Web pages are ghosts: they’re like images projected onto a wall. They aren’t durable. If you turn off the projector (i.e. web server), the picture disappears. If you know how to run a projector, and you can keep it running all the time, you can have a web site.

But as soon as there’s no one to babysit the projector, it eventually gets turned off, and everything you made with it goes away. If the outage is permanent, the disappearance is too. This is happening all the time, as servers fail, or companies are acquired and shut down.“When Yahoo! switched off the servers for GeoCities, the Web posting service, on Oct. 27, some 7 million of the Internet’s first websites went dark forever.” Time Magazine, 9 Nov 2009

I think about this a lot. And I’m not even thinking about the fate of the Entire Internet. Just the small sites I care about, the blogs and small publications. It’s sad to think that when their authors are gone, all their writing will eventually disappear. (And don’t tell me about the Internet Archive—that’s just another backup projector, run by volunteers. We have no assurance that it’ll still be running a year or ten years from now.) Then, too, I also think about my own web sites. Babysitting that projector can be a lot of work sometimes. If it’s all going to go up in smoke as soon as I’m unable to work on it anymore, then publishing on the web seems, really, quite futile.

The obvious contrast is with hard-copies: things written on paper or printed in books. We can still read books and pamphlets printed five hundred years ago, even though the presses that made them have long since been destroyed.

How can we give the average independent web writer that kind of permanence?

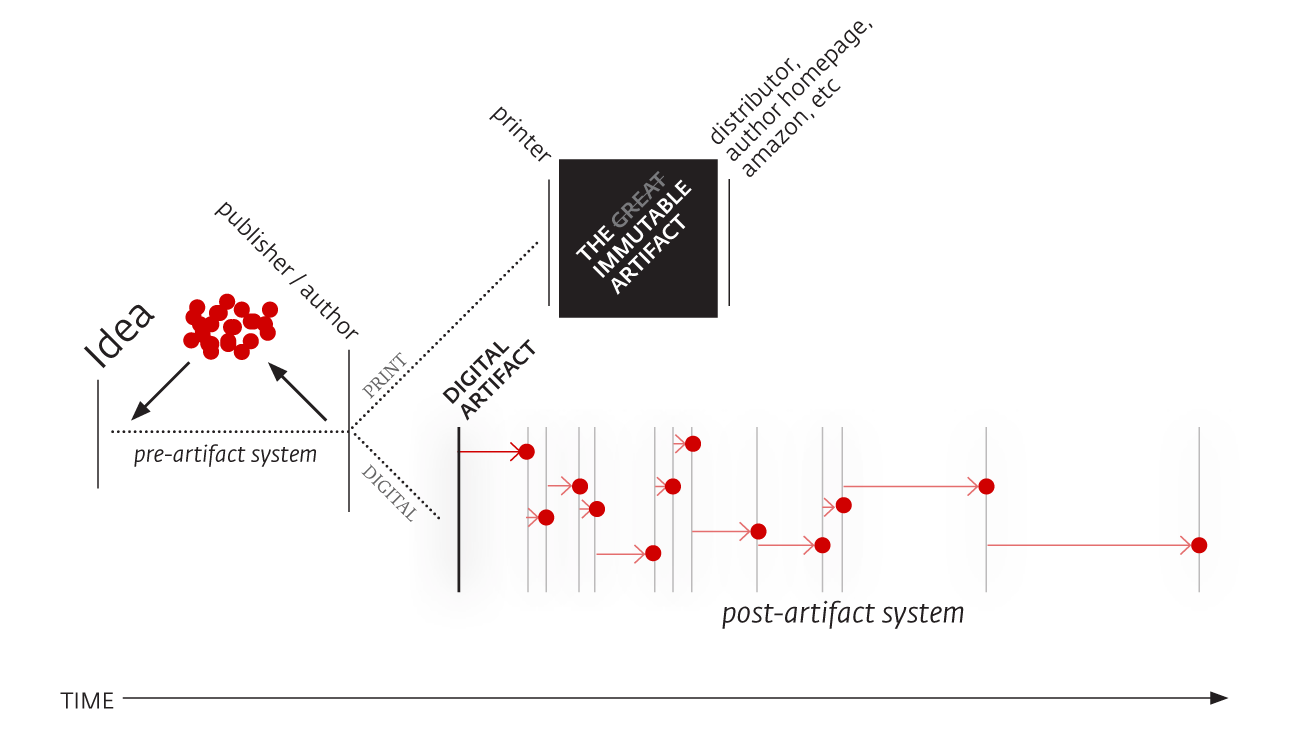

When Craig Mod drew this diagram, he was thinking about this issue the other way around. He was focused on traditional print publishing, and how the web would change that process. We started with print books, he said, and by adding digital publishing we can create this much fuller realm of author-reader interaction. It’s a brilliant and well-considered piece. It has this flip-side, though, which we web publishers don’t often talk about: books can be improved by the web, but the web can also be improved by books. Digital publishing could use more “Immutable Artifacts”, because artifacts are durable.

Of course there’s a reason why, in all our discussion about CMSs, about design, markup, semantics, and programming, we almost never include books. The tools we use don’t even consider book publication, much less integrate it. But they could. And that’s what this website, Secretary of Foreign Relations, is really about.

This site is basically a rough, first-effort experiment in creating a mini-publication that realizes both sides of Craig’s diagram above. It exists simultaneously as a web site and as a printed, bound book—a book that you can order right now and have delivered to your door.This being a basic proof-of-concept, the book’s cover is extremely generic, and the price is set as low as Amazon KDP will allow me to go ($5.38 in this case). At this point, only the content in the Flatland portion of the site is included in the print edition.

What do I mean by “exists simultaneously”? I mean that the production of the printed book is, for the most part, not some separate workflow from the production of the web site. I’m not copying text from the web site and pasting it into InDesign, for example. When I enter the command to generate the HTML files that make up this site, the complete PDF file for the book is generated at the same time, from the same source and by the same software.See more details on the Colophon page and on the project’s Github repository. I can upload this PDF file to Amazon KDP, who will print a copy for anyone who cares to order it.

Why a book? Of course anyone can load a web page in their browser and send it to their inkjet printer. But, seriously: no one does that, even for websites they feel quite attached to. Even if they did, and even if the printout looked really nice (very much not the norm for web pages), who wants to save a sheaf of loose papers? A book is the best kind of printed artifact, and with print-on-demand services you can have them made with reasonable quality at a very low cost.

So here’s how this will play out. After I reimplement my other web sites using this system, I’ll be making book editions of those sites available for free to anyone who cares to request a copyThis was what I had in mind originally with my Annual Yarn project, which I hope to resume.. This is a win for both sides. The reader gets a permanent, well-designed copy of something they have enjoyed. And I get the satisfaction of knowing those books are out there, being held in various places by people who (at least somewhat) care about them. The point is not to make money selling books, but to sow the writing as far as it can go—even knowing it has very narrow appeal and no market value. It’s a way to write purely for the joy of it, and still know that the work will easily outlive me. My writing will not depend for its continuance on someone maintaining backups and complicated hosting arrangements.

So much for my own stuff. But my larger, longer-shot hope is that others will start thinking about doing this too: building and making use of tools that integrate print publishing with web publishing. This goes back to the concern I talked about earlier. I don’t want the writing on small, independent sites to disappear. Not only do I want it not to disappear, there’s a good deal of it that I would like to have on my bookshelf. Some of those authors and those sites are gone already.“I don’t know Mark Pilgrim personally. I only know his work and it’s excellent. […] Mark is alive, but online he’s gone. He committed ‘infosuicide’ last week. All of his websites are Gone. That’s capital G, Gone.”—Scott Hanselman on the disppearance of Mark Pilgrim in October 2011. More are leaving all the time.

Whatever blogging tools or CMSs we use to publish on the web, we ought to start finding ways to have them generate well-designed books as well as web pages. The services and technology we need are already sitting there, ready to print those books for us. Supposing we were able to adopt this kind of approach, it’s easy to suppose we could develop a culture of sharing our books with each other. Our writing would be durable again. That would be a lovely thing.

Sonnet by John Keats

When I have fears that I may cease to be

Before my pen has glean’d my teeming brain,

Before high-piléd books, in charact’ry,

Hold like rich garners the full ripen’d grain…